Meeting Seed7

A strongly typed programming language. Interpreted and compiled. Performance in the ballpark of C. Memory-safe since decades. I feel embarrassed to admit that I had been totally unaware of Seed7 until mere two months ago.

With the growing adoption of Rust, memory-safety has come to prominence. It's not that we haven't had memory-safe languages before. In fact, memory safely is a commodity for managed runtimes like Java or C#, script languages like Python, Tcl, JavaScript, or Lua, and are a given in the worlds of LISP or OCAML. But those - informed people are quick to explain - are higher-level languages that usually rely on a garbage collector, somewhat disqualifying those languages for certain application areas like systems programming, for certain definitions of somewhat. The clever memory-ownership model of Rust eschews the overhead of garbage collection, thereby solving the long-presumed contradiction between memory safety and high performance. In this respect, it even goes beyond traditional integrity-concerned languages like Ada!

It turns out that long before memory-safety had become a fashionable topic at tinder dates, the problem had been identified and attacked by a programming language called Seed7. "Long before" as in three decades ago. "Attacked" in surprisingly lean ways.

- Seed7 homepage

When I first stumbled upon it earlier this year, the combination of static typing with interpreted execution caught my interest. Programs can also be compiled, thereby attaining performance in the ballpark of C. My curiosity was further piqued by its proclaimed memory safety without employing a garbage collector. I wondered, hasn't this been the key innovation and unique selling point of Rust's borrowing concept? How can a language rooted in the late 80s make such claims?

Off I went on a journey through the code and documentation of this project. There is hardly anything as stimulating to me as dwelling in the creations of a mind with an exceptionally fine taste. Seed7 is such a creation. It strikes me as beautiful on many different levels. Let me summarize a few.

|

A December Sunday well spent with crafting an LR-grammar for HID-syntax using the Seed7 interpreter ported to Sculpt OS running on the MNT Reform laptop.

The art of keeping complexity creep in check

The design of software often carries in its DNA the organizational structure of the team that created and maintains it. The incentives and economic playbooks behind software created by teams employed by multi-national corporations, founders of VC-fueled startups, demoscene artists, academic research teams, or hobbyists are vastly different after all. Those differences ultimately transcend into the software itself.

Seed7 is largely the brain child of a single individual, Thomas Martes from Austria, who steadily nurtures and maintains it independently as a long-time endeavour. Its scope has epic proportions, from the language design, compiler, interpreter, rich standard library, to the manual of 17.000 lines of text - pursued as one holistic vision. When viewed in an economic light, lean code structure, coherence, orthogonality, and simplicity are not mere ideals but necessities to sustain and enjoy maintenance.

For an example on the account of simplicity, Seed7 settles on a single 64-bit-wide integer type instead of supporting a variety of types like u8, s8, u16, s16 etc. I must admit that the disregard for making the most out of 32-bit CPUs seemed a little bit eccentric to me. But once when starting to use the language, one notices the complete lack of ceremony of converting and promoting integer types as a welcome relief.

Another striking example is the way how call-by-name parameters blend perfectly together with overloading and Seed7's extensible syntax, covering the most omnipresent use of lambda functions as a means for scoped execution. This is nicely exemplified by the for-range implementation in the xmldom library. When looking at this example, the declaration of nodeVar as an inout parameter surprised me at first. In C++ one would intuitively declare it as local constant in the inner loop, which is passed as argument to the caller-provided lambda function (statements), avoiding a mutable variable in need of a default value. However, the inout argument eliminates the need for any lambda-capturing syntax. It merely exposes a caller-site variable to the for function. That's all what's needed. How cool is that!

Memory-safety without escape hatches

Seed7 approaches memory safety with a straight reasoning: There are no pointers in Seed7. With no pointers, there cannot exist any dangling pointers. With no free function, there cannot be any use-after-free issues. In contrast to Ada/SPARK that follows this philosophy while disregarding dynamically allocated memory as outside the scope of the language, Seed7 acknowledges the need for dynamic memory management. But how can this work without pointers? Well, the answer is actually given by a whole lot of scripting languages, like Tcl, that offer just a few orthogonal dynamic data structures as building blocks. In Tcl, there are lists and dictionaries. In Seed7, there are dynamic arrays and hash maps. In contrast to usual scripting languages, however, those data structures are fully statically typed. The language runtime takes care of the lifetime and ownership of elements living in these data structures. Memory is not allocated manually, but an allocation just happens whenever adding an element to an array or hash map. The Seed7 programmer does not need to be cautious of it.

It goes without saying that this approach imposes an "upper ceiling" of the use cases of the language, which is ultimately constrained by the feature set of its runtime library. For example, unlike when using C++, one is not supposed to introduce special tailored allocators, or attempt to use a radix tree instead of the runtime-provided hash map. The term "ultimately constrained" goes two ways. On the one hand, it limits of what one can accomplish. On the other hand, it limits safety risks. Somewhere in the feature set of the runtime library lies the sweet spot between those both ends.

Unlike Rust that provides an escape hatch to safety with code marked as unsafe, for Seed7 the line between safe and unsafe is uncompromisingly the interface of the language runtime, specifically the so-called actions. An action is a function that cannot be expressed in safe Seed7 code and is therefore provided by the runtime library written in C. E.g., actions interact with the operating system, deal with raw pointers, interface with a bignum library, implement the array and hash map, or invoke foreign functions of a 3rd-party library. So "action" must be read as "unsafe". The runtime library provides a long list of actions, which I interpret as the documented surface of potential risks. In Seed7 this risk surface is curated by the author of the runtime library. It is deliberately not extensible by the Seed7 programmer without customizing the runtime. To me this makes perfect sense when looking at the management of risk as a responsibility. Where Rust's cargo opens the floodgates to the diffusion of responsibility as any 3rd-party crate (library) can extend the risk surface, the safety of Seed7 is only on the hinge of the runtime provider, clear-cut. One can argue that such a principled stance may stand in the way of adoption, but I perceive it as refreshingly upright.

Proof by construction

Speaking of the runtime and standard library, its vast feature set leaves me deeply impressed. It looks like the result of an extensive exploration and tireless pushing of the mentioned "upper ceiling". Where are the limits? Proving the language's fitness by giving evidence in the form of code that works. From crypto algorithms, TLS, compression formats, over parsers for a great variety of text and image formats, to database connectors, it is a treasure trove of useful and insightful Seed7 code. The delight I felt while studying the examples and the library ultimately prompted me to use Seed7 for a practical project.

Seed7 on Genode

On my current mission of converting Sculpt OS from the use of XML to an alternative called human-inclined data (HID), a formal grammar for HID syntax is desired. The formalization as an LR-grammar is not only an argument for the technical quality of the syntax but can also form the basis for implementing parsers for a variety of languages in a straight-forward manner.

For crafting such a grammar, Seed7 presented itself as the perfect testing ground. First, it is interpreted, promising quick experimentation cycles. Second, its standard library comes with many parsers from which I could learn. One particular lesson that I enjoyed more than I'd like to admit is the single bufferChar hosted in the file type. This detail turns the file the into a suitable abstraction for LR parsing. Simply delightful.

I could have used Seed7 on Linux. But given my affiliation with Sculpt OS, it goes without saying that I had to bring the interpreter over to Genode. For my little project, my interest lies with using the interpreter for a simple test program that reads a text file, parses the data, and outputs results. Given that I can live without the compiler and many features of the runtime like graphics or keyboard input, the experimental port of the Seed7 interpreter was accomplished in an afternoon by cowardly stubbing out everything that looked difficult.

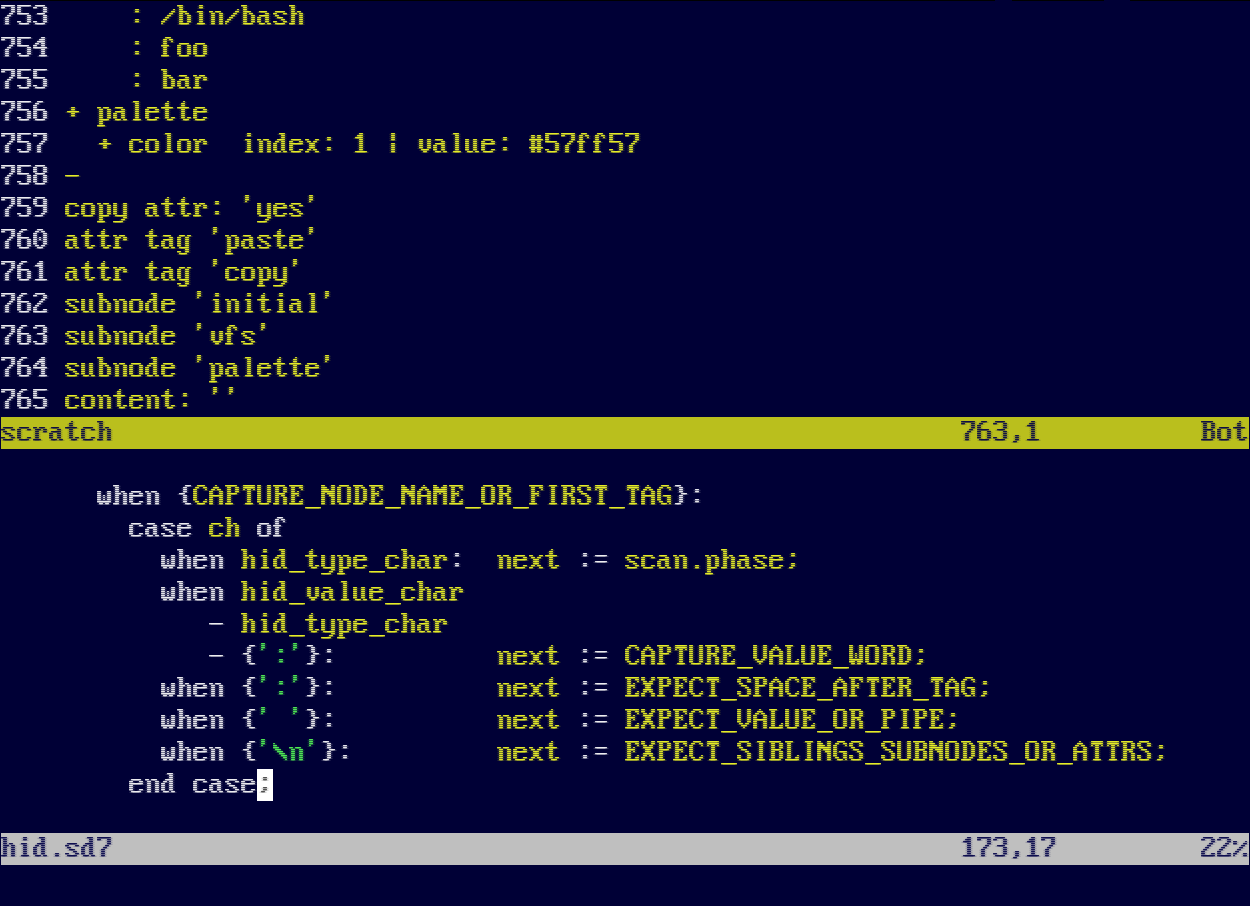

I'm not quite sure whether prompted by its particular syntax or by presenting itself as an somewhat endemic programming system with its feature-rich standard library, Seed7 invoked fond memories of using Turbo Pascal and spending days after days with exploring the help texts of the libraries (units) that came with it. The fascination of learning, the calmness of the process, the appreciation of the craftsmanship, me young. Giving way to this cozy nostalgic mood, I decided to paint my personal Seed7 "SDK" with aesthetics of my memories, using VGA text in saturated colors. A fun opportunity to use my custom BDF glyph renderer as a plugin to Genode's terminal.

|

8x16 glyphs zoomed by 2x2 on a full-HD laptop display nicely resemble a text mode of 120 by 33 characters. The glyph rendering, like the scanline effect, can be tweaked interactively.

The remaining puzzle pieces for interactively using the Seed7 interpreter on Sculpt OS are assembled in the form of the seed7-sdk package I just published in my Sculpt index "nfeske" in the "Programming" menu. Just wire up the "config" and "rw" file system to the recall fs to get started.

|

Vim as Seed7 IDE on Sculpt OS. The scratch window at the upper part of the screen presents the output of the program edited in the lower part. A press of F2 updates the scratch window instantly.

The package provides a development snapshot of my HID parser as an example project at /tmp/example/. To give it a try:

-

Change to the project directory via cd /tmp/example.

-

Open the source code in Vim via vim hid.sd7.

-

In Vim:

Press F1 to open the Seed7 manual.

Press F2 to run make and present the result in a scratch window.

Press F3 to close the scratch window.

You can find the Seed7 libraries and examples at /share/seed7/, and use the interpreter s7 to execute an example. E.g.,

/share/seed7/prg$ s7 dirx.sd7

You can interactively tweak the font renderer and colors to your liking by editing /config/terminal. The behavior of Vim can be tweaked at /config/vim.

Impressions

A couple of evenings and a few hundred lines of Seed7 code later, my HID parser works and the LR grammar stands. I thoroughly enjoyed the combination of the solidness of static typing with interpreted execution. The set type worked beautifully for my project. Given that I needed to define a data structure of nested nodes, I had to learn Seed7's approach to polymorphism at one point. Thankfully, the standard library provided all the guiding rails I needed for that.

I'm deeply fascinated by the breath and depth of the Seed7 project. I barely touched the surface. The story could go on with the language's natural looking approach to generic programming, or how Seed7 lays the compiler infrastructure into the hands of the programmer (code as data). The potential interplay of Seed7's file abstraction with the flexibility of Genode's modular VFS appears as a particularly intriguing territory to explore. What a joy to think of the possibilities!

Norman Feske

Norman Feske